We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Between his big-screen acting debut in Robert Rossen’s vastly underrated “Lilith” and his swan song “Welcome to Mooseport,” Gene Hackman had a reputation for being a prolific and, at times, nowhere-near-choosy-enough actor given his considerable talents. But when you look over that 40-year career, you don’t see an egregious number of turkeys. The Dan Aykroyd buddy-cop comedy “Loose Cannons” or his third go-round as Lex Luthor in “Superman IV: The Quest for Peace” are probably the twin nadirs of his career, but mostly Hackman had a propensity to make many mediocre movies watchable. He was the reason you’d find yourself halfway through Nicholas Meyer’s ho-hum spy thriller “Company Business” without any real complaints. Could it be better? Absolutely. But it had Hackman.

The movies — great, average, or garbage — haven’t had Hackman since 2004, which never ceases to stink. Now 94, there’s a good chance he would have retired in the 2020s if not before, but his former New York City roommates Dustin Hoffman and Robert Duvall are still plugging away. As long as he’s here, those of us who grew up knowing that every year or so there’d be at least one good Hackman flick hitting theaters can’t shake the hope that he’ll quietly step out of retirement for one blessed curtain call.

While you can never say never, the more you examine the reasons for Hackman’s exit, the more resolute you can be in the knowledge that his acting days are over — unless you can talk your way into his Key West estate. Let’s take a look back at his extraordinary career, and why he chose to call it a day when he did.

Gene Hackman’s rise and boil

Hackman began studying acting at the Pasadena Playhouse in 1956, which is where he met Hoffman. Neither performer was deemed worthy of success by their instructors and classmates, but a little over a decade later, both men were either full-fledged stars — like Hoffman via Mike Nichols’ “The Graduate” — or well on their way, like Hackman after his role as Buck Barrow, the hell-raising brother of Warren Beatty’s Clyde Barrow in “Bonnie and Clyde.”

Hackman’s journey toward stardom continued with his supporting turn as the U.S. Men’s ski team coach Eugene Claire in Michael Ritchie’s stylish sports drama “Downhill Racer,” and reached the station with William Friedkin’s “The French Connection.” Hackman’s portrayal of hard-charging NYPD detective Popeye Doyle is a problematic powder keg that rattles to this day. It earned him his first Academy Award (for Best Actor), and completely altered the trajectory of his career. Hackman wasn’t prone to the Method noodling of his American acting peers (including Hoffman); there was a bracing insistence to his performance, a yank-you-by-the-lapels violence that had you worrying for the welfare of everyone who came into contact with him.

This threat coursed through all of Hackman’s work going forward. He seemed like a bad man, and his characters were rarely comfortable with letting that kettle come to a boil.

Gene Hackman owned the 1970s and enlivened the 1980s

There was absolutely a comfortable violence to the butcher Mary Ann in Ritchie’s “Prime Target” and Sgt. Leo Holland in Bill L. Norton’s “Cisco Pike.” These films were Hackman in nasty mode, the pissed-off prelude to the cartoon malevolence of Lex Luthor in Richard Donner’s “Superman.”

Before Hackman got to supervillainy, he found dark shades of gray in three of his most fascinating characters: the itinerant Max Millan in “Scarecrow,” snooper Harry Caul in Francis Ford’s Coppola’s “The Conversation,” and private dick Harry Moseby in Arthur Penn’s “Night Moves.” These are men who don’t do well with the outside world; they’re screw-ups or defectives either tilting at windmills, or, in the case of Max, tending to the welfare of a doomed manchild.

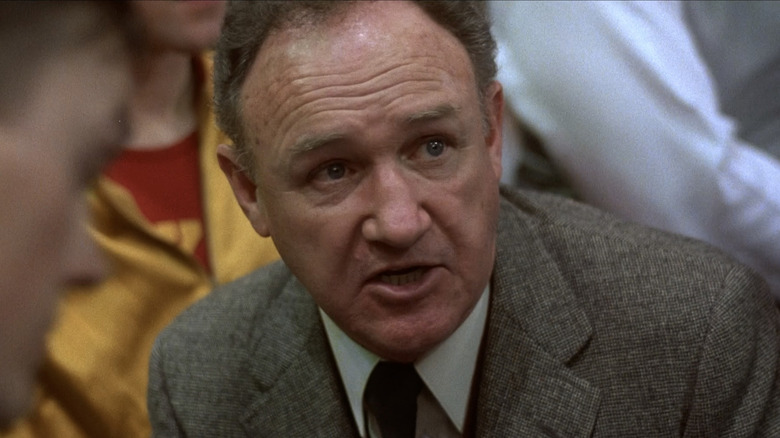

Hackman’s 1970s were stunning. There were trip-ups due to his frequent employment, but even a misfire like Stanley Donen’s “Lucky Lady” had merit. The 1980s were not so kind to Hackman, but this is due to his kinds of filmmakers, the lions of New Hollywood, getting cowed by the newly corporatized studios. Hackman was better suited to succeed in this climate than many of his 1930s-born peers if only because he could blend into just about any kind of movie. He didn’t need to devour; he just needed to eat his fair share, and move on to the next meal. And so, despite the gulf in terms of subject matter, there really isn’t much difference between “Uncommon Valor,” “Hoosiers,” and “Mississippi Burning.” He’s a gruff leader of men who believes in the toughest of love. It ain’t deep, but it sure is pleasing.

How Gene Hackman’s 1990s led to his 2004 retirement

The 1990s were more of the same, to a degree. Hackman was fine dispensing last-nerve affection to Meryl Streep’s addict actor in Nichols’ “Postcards from the Edge,” and at the very least engaged in Peter Hyams’ unnecessary remake of Richard Fleischer’s perfect “The Narrow Margin.” His bravura turn for the decade arrived early in Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven,” where he played the sadistic and ultimately unlucky sheriff Little Bill Daggett. Hackman’s the best thing in Sydney Pollack’s beyond bloated adaptation of John Grisham’s legal thriller “The Firm,” and suitably evil as a dedicated gunfighter in Sam Raimi’s “The Quick and the Dead.” But don’t discount his conservative politician forced into drag in Nichols’ “The Birdcage,” nor his Caul-recall in Tony Scott’s smashing “Enemy of the State.”

As for the 2000s, if he had to go out on one role prior to his (to be kind) game performance in “Welcome to Mooseport,” the part would’ve surely been the title patriarch in Wes Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums.” He was totally engaged in David Mamet’s twisty thriller “Heist” and David Mirkin’s rambunctious “Heartbreakers” opposite Sigourney Weaver, but the sizzle was starting to die out. After “Welcome to Mooseport,” Hackman was done with acting. And that’s because he listened to his body.

Why Gene Hackman retired

In 2009, the good folks at Empire landed a rare post-retirement interview with Hackman that serves as a moving and informative career retrospective. One of the most revealing moments in the chat found Hackman bluntly explaining why hung it up in 2004. “The straw that broke the camel’s back was actually a stress test that I took in New York,” said the two-time Academy Award-winning actor. “The doctor advised me that my heart wasn’t in the kind of shape that I should be putting it under any stress.”

In 2011, Hackman allowed that he could be persuaded to return to acting, but only under very specific conditions. As he told GQ, “If I could do it in my own house, maybe, without them disturbing anything and just one or two people.” No one’s figured out how to do that (it’s heartbreaking to note that the one director who might’ve convinced Hackman to give it a shot, Tony Scott, died far too soon in 2012), so we the screen has been Hackman-less for 20 years.

Gene Hackman’s retirement led to a second career as a novelist

Hackman has kept busy in his retirement. Aside from getting hit by a pickup truck in 2012 while he was riding his bike, he’s written five novels, which is a heckuva lot more than many working writers can say. Three of them (“Wake of the Perdido Star,” “Justice for None,” and “Escape from Andersonville”) are historical fictions penned with undersea archaeologist Daniel Lenihan, while the other two (the Western “Payback at Morning Peak” and the cop thriller “Pursuit”) were solo excursions.

Technically, he did come out of retirement to narrate the documentaries “The Unknown Flag Raiser of Iwo Jima” and “We, the Marines.” Just hearing that voice is a thrill. But the latter doc was released in 2017, which suggests Hackman is now good and retired, with zero exceptions. He owes us nothing. But selfishly, when you think about the instant credibility he could bring to a movie, you wonder what one scene in his Key West living room could add to the most mundane movie imaginable — i.e. one directed by Joe and Anthony Russo. On second thought, maybe being retired is better.